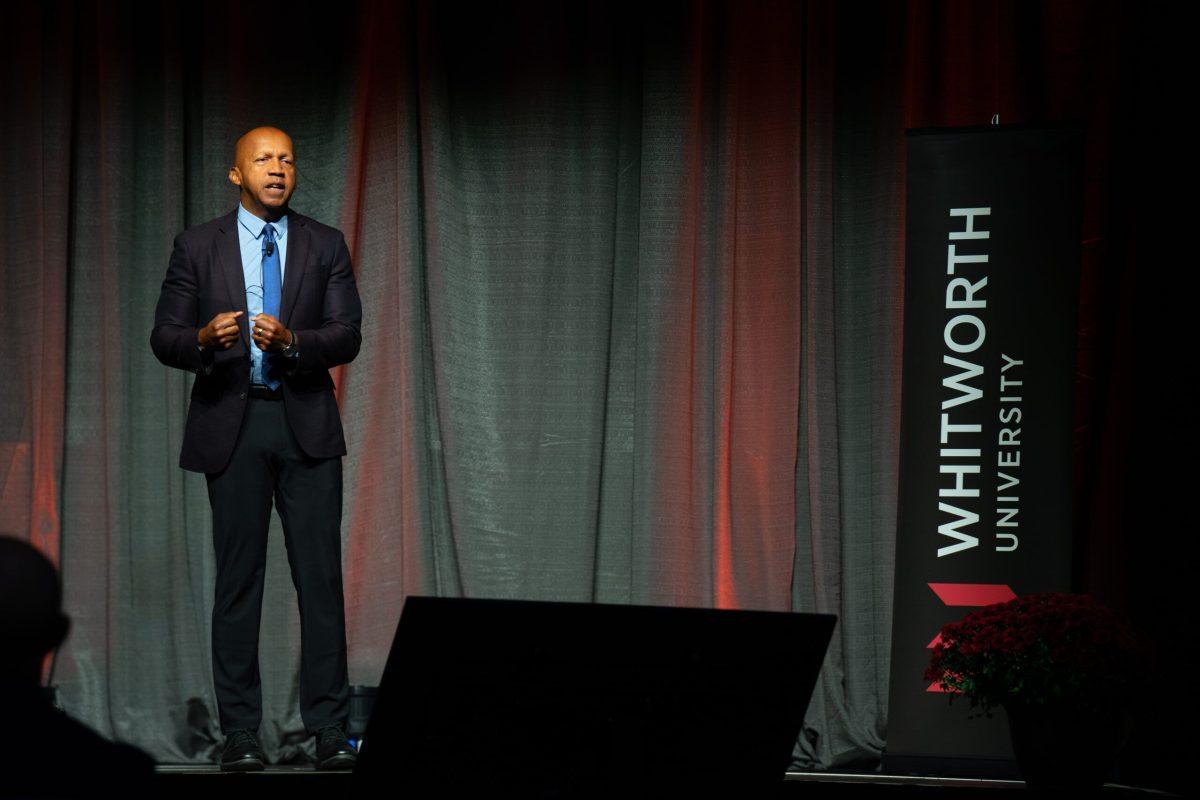

Bryan Stevenson spoke to a captivated audience on October 5 at the Spokane Convention Center. His message took the Micah 6:8 mandate “to act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly,” and discussed how it should inform our view on the incarceration system.

“In our country, it’s very easy to stay isolated from the problems, [but] we have to get closer to the people who are struggling,” said Stevenson.

The problem of the incarceration system’s impact on people has risen dramatically, said Stevenson. Before the 1970s, less than 300,000 people were in the United States incarceration system. Now, there are over 2 million people, and the U.S. has the highest levels of incarceration in the world.

This is due to the U.S.’s “commitment to incarceration and punishment – extreme punishment,” said Stevenson.

He again emphasized the need to “get proximate” to the issue.

Getting close enough to people to hug them is a representation of the need to get close enough to people “to affirm their humanity,” he said.

This ability to get proximate to issues has had a direct impact on Stevenson’s own life, he said. His ability to get a quality higher education was a direct result of the Supreme Court decision from Brown v. Board of Education. This helped Stevenson because there were lawyers proximate to him who were willing to enforce the Supreme Court’s ruling for Stevenson’s benefit.

Once he got to law school, he further realized the power of proximity. He shared about a time he was told to inform someone on death row that their execution would not happen within the next year. The incarcerated individual was thrilled to hear the news, and he and Stevenson talked for a few hours.

“There’s power in proximity,” Stevenson said, referring to how he could brighten the man’s day just by being around him.

Stevenson challenged the audience to think about the narratives that shape the world, saying that many problems arise when we use narratives of fear and anger.

The language we use can greatly impact these narratives, said Stevenson. As an example, he said when communities began labelling incarcerated children as “super predators,” it became easier to charge them as adults for crimes they had committed. Sometimes, this resulted in children being jailed for years.

“Who’s responsible for this?” he asked. “We are.”

“The narrative has to change,” Stevenson said. People need to start caring for all kids – especially those who are the poor and marginalized, said Stevenson.

He said that injustices cannot exist without a narrative that justifies them. If we are to change injustices, we must change the narrative.

He also challenged the audience to be hopeful about their potential to create change. He shared a story about his grandmother, who would encourage him to read at every turn. She once gifted his family a set of World Book Encyclopedias for Christmas. His childhood experiences taught him that education is an act of hope.

Stevenson ended by urging the audience to be willing to do uncomfortable and inconvenient things. He told a story of a man he had met after giving a speech. The old Black man had proudly shown Stevenson the bruises and cuts he carried.

The man explained that his cuts were “medals of honor” that he had won while registering Black people to vote in different states. These, Stevenson said, are the types of medals of honor we get when we get proximate to an issue.

Throughout the talk “the audience was captive,” said Scott McQuilkin, current president of Whitworth University.

“His messages are compelling,” McQuilkin said. “He appeals to our convictions of justice and mercy and humility.”

McQuilkin also heard Stevenson speak at the Equal Justice Initiative during the summer of 2023. McQuilkin said he was so inspired by Stevenson’s summer talk that he immediately decided to offer free President’s Leadership Forum (PLF) tickets to local students at law schools, colleges and universities and high schools. He thought offering youth the ability to hear Stevenson speak was a “worthy thing to do.”

At the PLF, McQuilkin awarded Stevenson with an honorary doctorate from Whitworth University. McQuilkin also announced that Whitworth was creating the Bryan Stevenson Endowed Scholarship. This endowment of $50,000 will give out one $2,000 scholarship per year.

In recent years, the PLF speaker has appeared at three events: the forum at the Spokane Convention Center, a reception for sponsors and a speaking event at Whitworth for the faculty, staff and students. This year, due to Stevenson’s tight schedule, he was only able to speak at the Spokane Convention Center and the reception.

McQuilkin said securing Stevenson as a speaker has been “a two-and-a-half-year pursuit.” While Steveson had been the PLF speaker back in 2015, his rise in popularity had left his schedule much busier.

Next year’s PLF speaker will be Elizabeth Cheney, who will be speaking in October of 2024.