In the wake of the civil rights movement, a guest lecturer called Whitworth University a “white ghetto” for its complacency and lack of diversity. Almost 60 years later, conversations surrounding diversity are still prominent at the university.

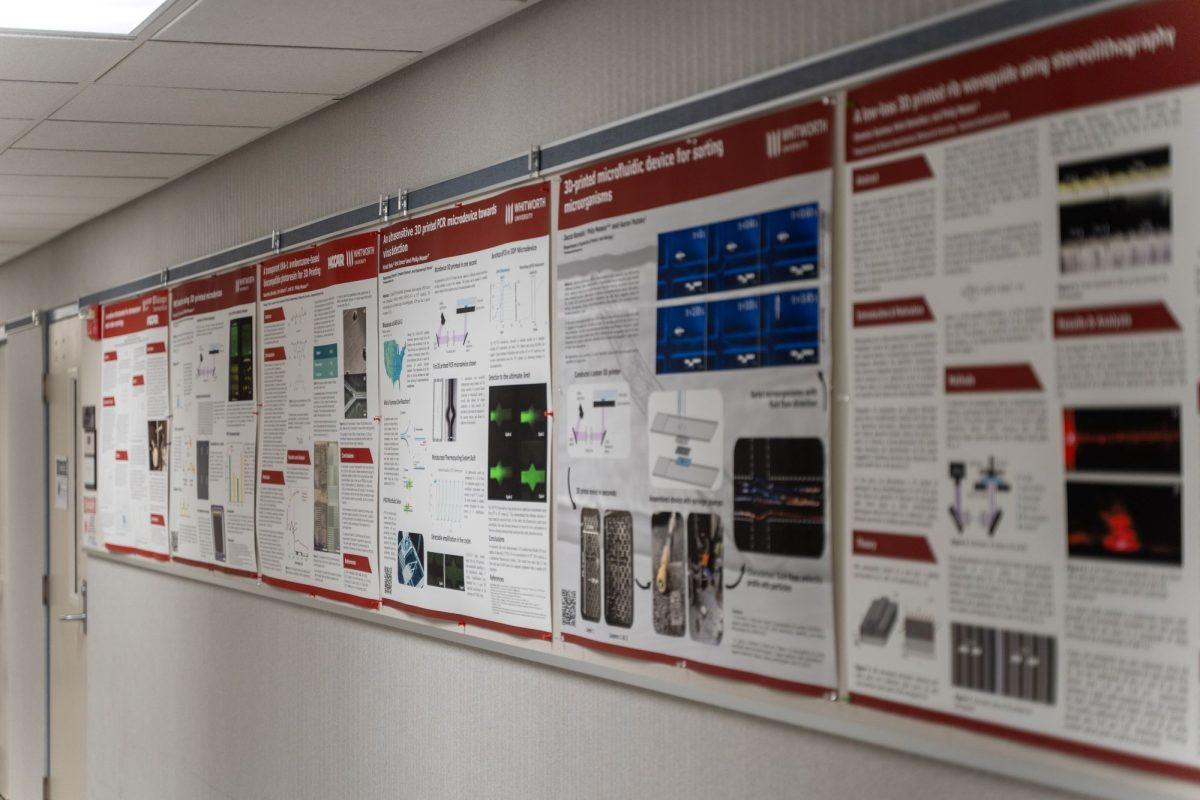

On Tuesday, Feb. 13, Dr. Dale Soden gave a lecture in the Robinson Teaching Theater entitled “The History of Race at Whitworth.” Soden is a professor emeritus of history and was regarded as “Whitworth’s historian” by Joshue Orozco, vice president of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. This lecture was the second of three educational lectures taking place for Black History Month this February.

Soden divided the lecture into four parts, or eras, of Whitworth history: the first era, 1890-1965: Exceptional Individuals and a Culture of Assimilation; the second era, 1965-1970: The Influence of Civil Rights and Black Revolution on Campus; the third era, 1970-2000: The Struggle to Become More Diverse at Whitworth and the fourth era, 2000-present: Act Six, Ongoing Struggles and Exceptional Leaders. For each of these eras, Soden highlighted influential members of the African American community throughout Whitworth’s history, including the first black Whitworth graduate in 1936 and influential black leaders in Whitworth’s community today.

In his section on the second era, 1965- 1970, Soden highlighted two particularly influential events that happened on campus during the 1966-1967 school year. The first was a talk given for Spiritual Emphasis Week in 1966 by lay theologian and attorney William Stringfellow, who called out Whitworth’s complacency in civil rights issue by calling the school a “white ghetto.” Stringfellow is quoted in the Winter 1967 Campanile Call as saying, “You are the educationally deprived. […] Just look at the churches you belong to now. Just look at the colleges you attend. Just look at the appalling complacency and apathy and silence and feigned non-involvement. […] Just look at that. And then, if you want to become very specific about it, look in the mirror.”

Stringfellow’s use of the term “ghetto” in this context refers to the segregated or uniform whiteness of Whitworth in 1966 and does not necessarily refer to poverty as the term is contemporarily understood. As the civil rights movement was beginning to take off, white students at Whitworth were turning a blind eye to the struggles of their black neighbors.

However, Stringfellow’s criticism of the university did not go unnoticed. In a Whitworthian publication from Dec. 14, 1966, student Ross Anderson wrote that “By awakening students, faculty and administration to the reality of Whitworth’s “white ghetto,” Stringfellow lit a fire of awareness and action in many people.”

Soden then pointed out a response from one of Whitworth’s six black students at the time. Student Jeff Tucker wrote a letter to the Whitworthian editor, which was published in the same 1966 publication. In his article titled “The White Fool’s Dream,” Tucker said that “Whitworth has a white problem. There are too many white students and not enough [black students]. Because of this, the few black [students] here suffer.” Tucker went on to say that “Each [black student] is put on display under the ‘we got some too’ slogan. Instead of being an individual, he is all [black students]. Tucker continued with “the [black students] at Whitworth [are] tolerated, but not accepted.”

Tucker used his experience as a black student at Whitworth to support Stringfellow’s call to support students of color. He said that as a Christian college, Whitworth should be especially focused on recruiting low-income minority groups and making room at Whitworth for them. “It’s one thing to help more [black students] get an education, but it’s another thing to make them feel really wanted,” said Tucker.

It is clear from both Stringfellow and Tucker’s writings that Whitworth was struggling to be a place of diversity during the 1960s. But what does the university look like now?

“My general takeaway [from the lecture] was that although Whitworth has come a long way regarding race relations, […] more work needs to be done before a sense of accomplishment can be felt on campus,” said Andrew Lubben, co-president of Whitworth’s Black Student Union (BSU). In response to Stringfellow’s “white ghetto” quote, “I found myself completely understanding what Stringfellow meant. As not only a student of Whitworth but a lifelong resident of Spokane, I resonated with his sentiment,” said Lubben.

However, even at a liberal arts school, “Students who do not study the humanities will miss out on that diverse learning experience that Stringfellow was criticizing Whitworth for not having,” said Lubben. Humanities and social science classes are at a unique advantage in that their disciplines often directly study race relations, while Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) classes are less likely to do so simply due to subject matter.

While students in STEM classes are not taught directly the history of race in classes, “diversity comes in different angles,” said Dr. Kamesh Sankaran, professor and chair of Whitworth’s engineering and physics departments. It is the “disciplines themselves [that] are cross-cultural,” said Sankaran. STEM departments differ from humanities departments in that they are universal. “Mathematics is mathematics all over the world,” said Sankaran. Humanities departments have a variety of different methodologies and interpretations that can change based on where in the world these topics are being studied.

Dr. Aaron Putzke, professor and chair of Whitworth’s biology department, supports Sankaran’s claim. Biology is “all about diversity, whether it’s plants or fish or humans,” said Putzke. The goal of a liberal arts university is “to create holistic thinkers,” said Putzke, which includes teaching about diversity within the STEM classrooms.

Returning to Lubben, STEM and humanities departments certainly have different ideas of what it looks like to teach diversity. However, it seems that almost all departments at Whitworth are taking steps to include diversity in the curriculum. As a liberal arts school, there is also space for students to take classes outside of their disciplines to glean knowledge about topics they feel are lacking in their own departments.

Soden’s lecture highlights important growth in Whitworth’s ability to address racial inequalities on campus. However, this does not mean that the conversation is over. As Lubben said, “Whitworth has come a long way regarding race relations, [but] there is still a general feeling among the staff and student body that more work needs to be done before a sense of accomplishment can be felt on campus.” What accomplishment looks like is different for everyone. But it seems safe to say that the university has moved away from Stringfellow’s “white ghetto” and pivoted toward a more diverse approach to education.

*The quotes have been altered to use appropriate language when referring to black students and other students of color.