The death penalty has to go, Sister Helen Prejean said to a packed house at Gonzaga University Oct. 11.

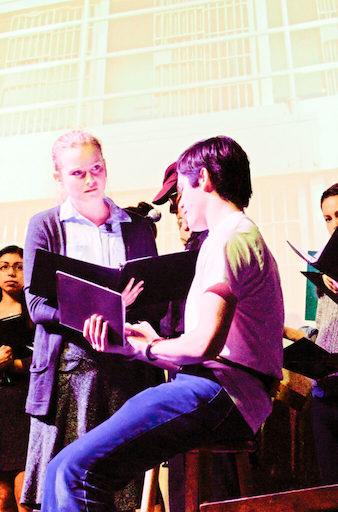

A live rendition of “Dead Man Walking,” Prejean’s nationally-acclaimed book documenting her first experience with capital punishment, kicked off the night. The show follows Prejean, a nun from Louisiana, in her formation of an unlikely friendship with a man convicted of the rape and murder of two teenagers.

At the time, the man was months away from his execution in Angora Prison’s death row.

Students from Gonzaga, Whitworth, Washington State University and Rogers High School performed in a one-act theatrical reading of Prejean’s story preceding her lecture.

Members of the Fellowship of Peace foundation, a local advocacy group recently founded by long-time anti-death penalty activist Victoria Thorpe, coordinated the event.

Fellowship of Peace brought the topic to Spokane students because of the potential legislative influence of Spokane County as well as the ability young people have to embrace varying viewpoints.

“Youth have the vitality and the energy and the hope for the future to really change something,” Thorpe said.

Thorpe has been seeking to end Washington state’s death penalty for the past five years. Many Washington residents, do not even know the state has a death penalty, Thorpe said.

“These are modern times now,” Thorpe said. “We should think of some other options because we have other options.”

The death penalty has long been a part of the U.S. legal system. It has been held up as a deterrent to crime, but Whitworth political science professor and lawyer Kathryn Lee said she questions its effectiveness.

“Often times people are killed or murdered in crimes of passion or an impulsive act,” Lee said. “Usually people are not doing a cost-benefit analysis when they’re killing someone.”

The lack of analysis by a person committing murder prevents the threat of capital punishment from being an effective deterrent to crime, Lee said.

“If we wanted it to be a deterrent, then why don’t we put executions on television, rather than at midnight and only 20 people view it?” Lee said.

More than pragmatic reasoning, moral reasoning has dominated the death penalty debate. One of the main questions Prejean, Thorpe and Lee all presented was: Does the state have the right to kill?

“Once you’re out of imminent danger you don’t have the right to take someone’s life,” Thorpe said. “We’re telling the government to do what we’re not allowed to do.”

The main moral argument for the death penalty presents retribution as the most basic form of justice, Lee said. In the view of death penalty supporters, the only way to establish justice and society’s value for a taken innocent life comes through taking the life of the murderer, she said.

In the play, the moral tension between the opposing viewpoints comes to the forefront by directly contrasting crime and punishment. Under a blue light and surrounded by candles, the play’s penitent murderer was put to death while scenes of his crime were revealed beneath a harsh red light, accented by the cries of his victims.

Prejean did not shy away from discussing the friction between sympathizing with both a criminal and his or her victims.

“It’s ethical to be outraged at the death of innocent people,” Prejean said

This outrage, however, does not justify capital punishment, she said. For this reason, Prejean has continued to build friendships with people on death row.

Since her experience in Angora Prison, Prejean has accompanied six men to their deaths. These men were by no means heroes, she said, but they were human beings and deserved dignity in their deaths.

Contact Weston Whitener at wwhitener17@my.whitworth.edu

Note: A correction was made to this story to clarify Lee’s explanation of the view of death penalty supporters. The Whitworthian incorrectly stated Lee believes the death penalty provides justice. The comment was not her personal view, but instead her perspective on the view of death penalty supporters.

Spokane?

Spokane?