On Jan. 20, 2018 at around 8:05 a.m., an Amber Alert was sent out across Hawaii detailing a ballistic missile attack headed towards the state. At the time a group of 27 students and two faculty members from Whitworth were in Mokulēʻia, O’ahu for the month of January. They received the message while they were eating breakfast and preparing for an exam later that day. At the time of the receival, the professors took cautionary action, informing all the students about the warning and asking them to gather important items from their rooms before quickly heading to an emergency site. The group loaded into their van, pausing for a moment to pray before driving to the local high school. The professors were trained on the protocols for many emergency situations and knew the high school would be the best location to go in case of an attack. Once the students and faculty arrived, they awaited further confirmation of the missile. Some students contacted parents, friends, and relatives to say goodbye while others debated whether or not to.

“How do you react if you have thirty minutes to live?” freshman Chris Roberts said.

About 38 minutes into the alert, the group received another message: “There is no missile threat or danger to the State of Hawaii. Repeat. False Alarm.”

Upon returning to the camp after the false alarm report, the professors gathered the group together to debrief, inviting the students to talk about what they were dealing with or share how they felt throughout it all, said multiple of the students. Some students offered to listen and help others work through their responses.

One of these students, freshman Rachel Coy, said that she felt calm throughout the incident, more concerned for how her fellow classmates were dealing with it than herself.

“I was so proud of our students because they were so composed. Nobody freaked out. They cared about each other very well and made dealing with that situation about as positive as it could be,” said Ron Pyle, professor of the month-long interpersonal communications course.

Pyle said that he did not think about calling his kids until after the threat ended because he was focused on what he needed to do for the students.

“What flashed through my mind was, ‘If this is real, I’m living a [fundamental] turning point in world history,” Pyle said.

Without the support of professor Terry McGonigal and his wife, the experience wouldn’t have been the same for Pyle, he said.

Pyle said the group took time to pray again after the debrief, and the students were allowed time to reflect and respond to the event in whatever ways they needed to. Freshman Laura Waltar said she watched the waves and called her family after the event, and Roberts said the professors allowed the students the rest of the day to take their test without stress.

“It was all super fast. We got back to camp, and we just went right back to breakfast. Our food wasn’t even cold yet,” freshman Justin Li said.

He sent a few messages to his parents during the evacuation and another when the threat had been disproved. Li’s parents did not see them until after the alert had settled, leaving them more relieved than concerned, he said.

Li said multiple students explained that their friends and family heard about the circumstance after the threat had been settled, but many others contacted their family throughout the incident.

Freshmen Kristopher Seumanutafa-Noa and Faith Kahulamu, both native Hawaiians, were also in Hawaii when they were woken up by the Amber Alert message, they said. The students were in one of the families’ homes when Kahulamu’s phone vibrated. Immediately she woke Seumanutafa-Noa, telling him to call his parents and showing him the notification. They gathered with the rest of the family and waited.

“What you have to do is just stay inside the house and wait until something happens,” Seumanutafa-Noa said. “That was the longest thirteen minutes of my life, and we just sat there; just waited until something happened.”

After checking in on his parents Seumanutafa-Noa described reaching a point of acceptance, faithfully believing that, “No matter what, we would just see each other again.”

Kahulamu’s response was similar: “So many people were getting prepared to die…The entire world was different for [thirteen] minutes.”

However, Kahulamu said she would rather have been in Hawaii with her family than anywhere else, knowing they were all doing whatever they could and getting to talk to each person one final time.

“It gives you a new sense of things…You look at everything differently…You realize what’s important, and things that used to stress you out are nothing,” Kahulamu said.

There was a wide range of responses from students throughout the entire incident; some felt emotional while others remained calm, said Roberts. Many agreed it was an experience that brought the group closer together and gave them a new perspective on the rest of the trip. When asked to select three words to describe how they felt during the experience, the responses were all different.

Li described it at surreal, tense, and scary. Waltar, on the other hand, described it as caught-off-guard, peaceful, and reflective.

Pyle said he felt very proud of the group and relieved when the threat settled.

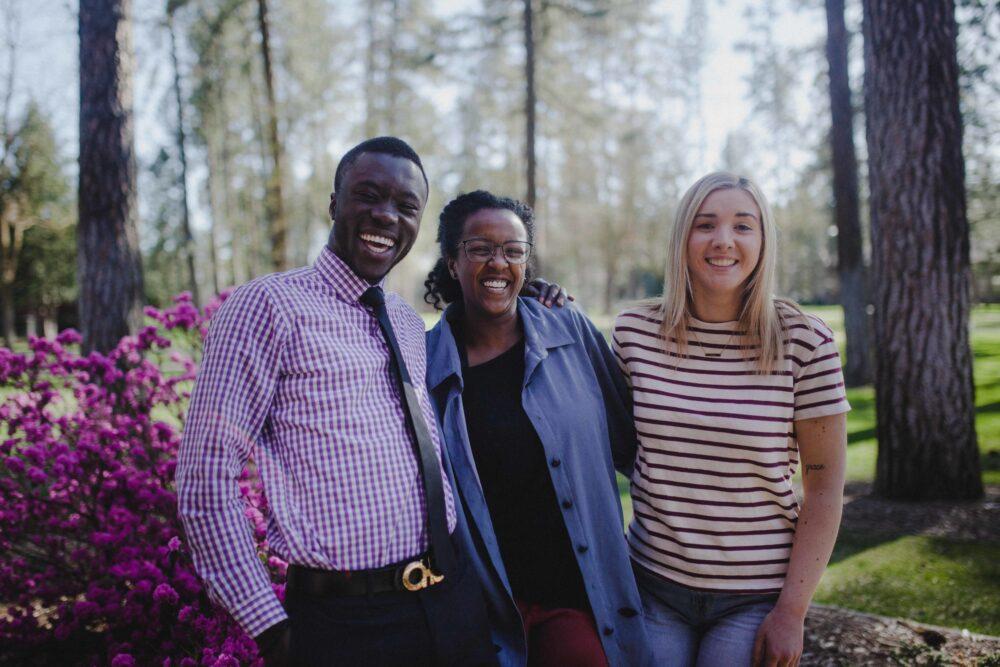

“That sense of togetherness has never been there at any other point in my life in a similar situation,” Sanjay Philip, a freshman on the trip, said.

Waltar saw the missile threat as an unexpected, humbling circumstance that brought many close together and allowed one another to think more reflectively about life. The professors, Ron Pyle and Terry McGonigal, encouraged their students to think about certain questions such as, ‘Where do you find security in an unsecure world?’ and, ‘What ultimately matters?’, and students connected with each other through prayer and conversation, Pyle said.

“If I were going to go with a class and have that happen to me again, I would choose those same people, and I would be so glad that we’d taken that amount of time, and we’d bonded so much,” Philip said. “Everyone’s come back with a new piece of them, and they’ve brought that to their friends and their family, and that’s been really important.”