One of the greatest critiques of American public education is that it fails to adequately prepare American students to compete on a global scale. However, even as there are those who consider education reform a pressing issue, others assert that the education system doesn’t need any major reforms because the true source of trouble lies elsewhere.

This brings us to the topic of educational standards, or more specifically, the question: will changing standards really help improve the American education system?

The answer is no. Some attribute the struggles of current education to previous or new standards. They are mistaken. These issues have existed for some time, and the true solution lies not in nationalizing curriculum standards.

“American education needs to be fixed, but national standards and testing are not the way to do it. The problems that need fixing are too deeply ingrained in the power and incentive structure of the public education system, and the renewed focus on national standards threatens to distract from the fundamental issues,” wrote Lindsey Burke and Jennifer Marshall in a 2010 article for the Heritage Foundation.

There are two key elements that need to be addressed.

One of these fundamental issues is that knowing the answer has become more important than learning the processes that were used to find it. Learning has become secondary to competition—between schools for funding and students for becoming “successful.” Students need to understand what and, equally important, why they’re learning so that they can master it. Because once mastered, they can innovate—they can create new techniques, processes and ideas in that area and develop as individuals as well as scholars.

An accompanying critique is that of lasting student dependency. Learning relies heavily on the thoughts and knowledge of others, that is inescapable fact. All current academic knowledge is based on what our predecessors have discovered. However, in the current system, students’ thinking has become lastingly dependent on others. Learning is suppose to prepare individuals for independent thinking, so that they can continue to problem solve, even in new scenarios. The earlier innovative thinking is cultivated, the better.

Pasi Sahlberg, a well known Finnish education expert, said that the question the U.S. should be asking is not, “What will help students succeed in today’s economy,” but rather, “What will make them be lifelong learners?” (as cited by Linda Borg of the Providence Journal).

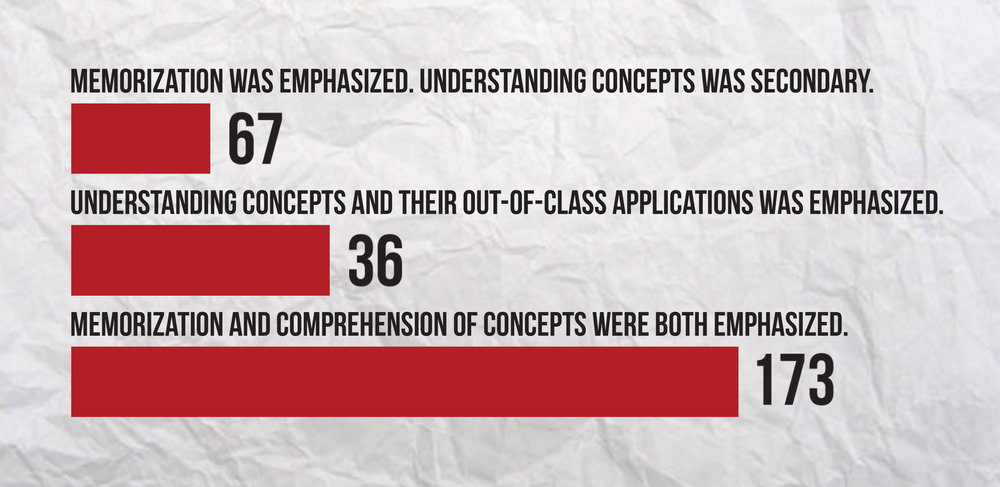

While this is certainly an area that needs to be addressed, it may not be as widespread as one may fear. A survey conducted by The Whitworthian found that of the 276 respondents, only 24 percent reported that their high schools’ learning methods emphasized memorization over comprehension of concepts and their out-of-class applications. The small and isolated pool may not accurately represent national and state averages, but one can hope that in most regions the majority of students experience a focus on comprehension and application.

This problem is one that must be addressed in the classroom. It is connected to the teaching methods districts and educators employ: how they teach, not what curriculum they are required to teach. Standards cannot dictate what aspects of learning teachers choose to emphasize on a day to day basis, even if they try to, because a level of teacher autonomy will always be retained. What aspects of schooling are emphasized as the most important is up to their efforts and methods. The solution to this problem, and something that Whitworth can supply, is more qualified educators.

So why all the fuss about fixing American educational standards? One of the most consistently cited indicators of the poor quality of American education is its ranking on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), “a triennial international survey which aims to evaluate education systems worldwide by testing the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students,” according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The 2012 PISA (the most recently published) reported America to be below average in mathematics and close to average in reading and science, according to OECD.

This brings us to the second, and more significant of the two, fundamental issue for improving American education.

State standards, teachers and students have all been blamed as part of the apparently poor state of American education. Finland is often cited as an ideal model for America to emulate, said scholastic writer Wayne D’Orio, as it consistently ranks at the top of the global scoreboard. However, the cause of America’s global ranking has been tied to another culprit, one that would also shed new light on the accuracy of the ranking.

David Berliner, the Regents’ Professor Emeritus of Education at Arizona State University, has authored and co-authored many studies and books addressing various aspects of education. He argues that the reason America has scored poorly on the PISA is because of the achievement gap in U.S. schools. Poverty, not the quality of teachers or the curriculum, is the cause of low global scores.

“American schools with fewer than 10 percent of students in poverty score higher than any country in the world. It continues from there: Schools under 24.9 percent rank third in the world and schools from 25 percent to 49.9 percent rank tenth and still above the PISA and the U.S. averages. . . 50 to 74.9 percent of students in poverty score low; schools with over 75 percent of students in poverty have reading scores so low they outrank only Mexico,” wrote Malcolm Terence of the California Federation of Teachers, citing data from Berliner’s research.

The most significant factor to student achievement is poverty. If such data is accurate, standardizing education will not change how America scores globally because it is not addressing the root of the problem.

Poverty is an eternal struggle, and is itself a consequence of other factors. It likely will never be eradicated on this earth, but it can and should be fought, especially when concerning education. If America is to develop intellectually and humanitarianly as a society, improving the lives of impoverished students needs to be prioritized so that the bottom line of student achievement can be raised. Education is a hand up, not a hand out.

Contact Matthew Boardman at [email protected]